Managing technical debt

The beginning of my career was blessed by the fact that I never really had to deal with code that other people had written (at least not directly). When I began my career, I started off working at an agency, and if you’ve ever worked at an agency before, you’re aware of the fact that the work is primarily project based. Meaning, once I was done writing the code for a specific project, I wasn’t on the hook for maintenance (there was no technical debt that I ever had to pay down). This sounds great, but there were trade-offs with this no tech debt way of working; hardcore deadlines and sleepless nights being but two of the negative aspects of this kind of project work.

Even when I transitioned to being a product developer at Mastercard, everything I worked on was greenfield; I started everything from a clean slate. I was fortunate in this regard — I didn’t have to deal with technical debt for a large portion of my career 😏! “However, when I was eventually confronted with technical debt in the real world, I was utterly astonished by the extent of its presence in numerous high-profile applications and businesses.

So let’s talk a little about how I learned to manage, mitigate, and pay down technical debt 🙏🏽!

What Is Technical Debt

Technical debt, at least in the context of this blog post, refers to decisions that engineering teams make in order to expedite the delivery of features. At a granular level, continuing to use and expand up class components that exist in a React codebase instead of trying to write new components using hooks (reusing old outdated patterns) is a decision that adds technical debt. At a higher level of abstraction, continuing to work with and utilize a custom built fullstack framework (that is poorly documented) instead of using a prebuilt solution like NextJS or

Remix is another form of technical debt. Don’t get me wrong, the custom built solution works… but it’s clunky and hard for to reason about and this very same thing can be said about React class components.

Now, why do we call technical debt “technical debt”? Well, similar to debt in the real world, technical debt accrues interest and the longer that we wait to pay off this debt, the more the interest will compound. Now the interest I’m referring to isn’t monetary in nature (like that of your mortgage 😅) but a more intangible interest. This “interest” results in engineers spending more time fighting with the codebase instead of actually focusing on delivering value to users. As the technical debt accrues interest, it becomes increasingly more frustrating and tedious for engineers to work on solving problems; their focus shifts from “let me deliever value” to “please lady luck, don’t let me break anything during my deployment”.

Please keep in mind, I’ll be talking about technical debt and how I’ve seen it manifest inside frontend codebases. I’m sure the discussion I’m having below will be applicable to other parts of the stack but since I am a frontend developer (at least for right now), I’ll be focusing on the frontend.

Paying down the Debt

By this point, we should all be on the same page about what technical debt is (at least at a high level), and the next obvious question is, “now what”? My trite response is let’s talk about figuring out how to go about paying down this debt.

Last year I was exposed to a method in which a team can pay down technical debt whilst still continuing to deliver value to their users. Oftentimes, our initial visceral reaction to projects with severe technical debt—and this used to be my reaction too by the way— is to treat them like Frankenstein’s monster… our prescribed remedy is cleansing by fire 😆. While it would be great to be able to start a project from scratch and rebuild an existing application from the ground-up, sometimes it just isn’t feasible. What do you mean Taran? We’re engineers! If we can dream it, we can do it! Well yes, you’re right, technically anything is feasible but I’m not only talking about technical feasibility.

Rewriting an entire application or sometimes an entire host of applications with a brand new shiny framework just not make sense for the business, especially if the business is risk averse. Writing software takes time and if you’re rewriting software and functionality that already exists, it’s really tough to get buy in from senior leadership that this is indeed required. Unless your technical debt is so much so that it endangers the scalability of the business, I highly doubt one would be able to sell a proposal for a rewrite up the entire chain of command — your manager might just stop you before you even try to convince anyone else that it’s a good idea. Don’t forget, the time we spend working on one thing is time we’re spending not working on another thing.

Time is money, money is power, power is pizza, pizza is knowledge, let’s go.

-April Ludgate

So what is an engineer to do? How do we deal with this technical debt, especially if the organization that you’re working with is totally against a ground-up rewrite. The answer: a phased migration!

Phased Migration

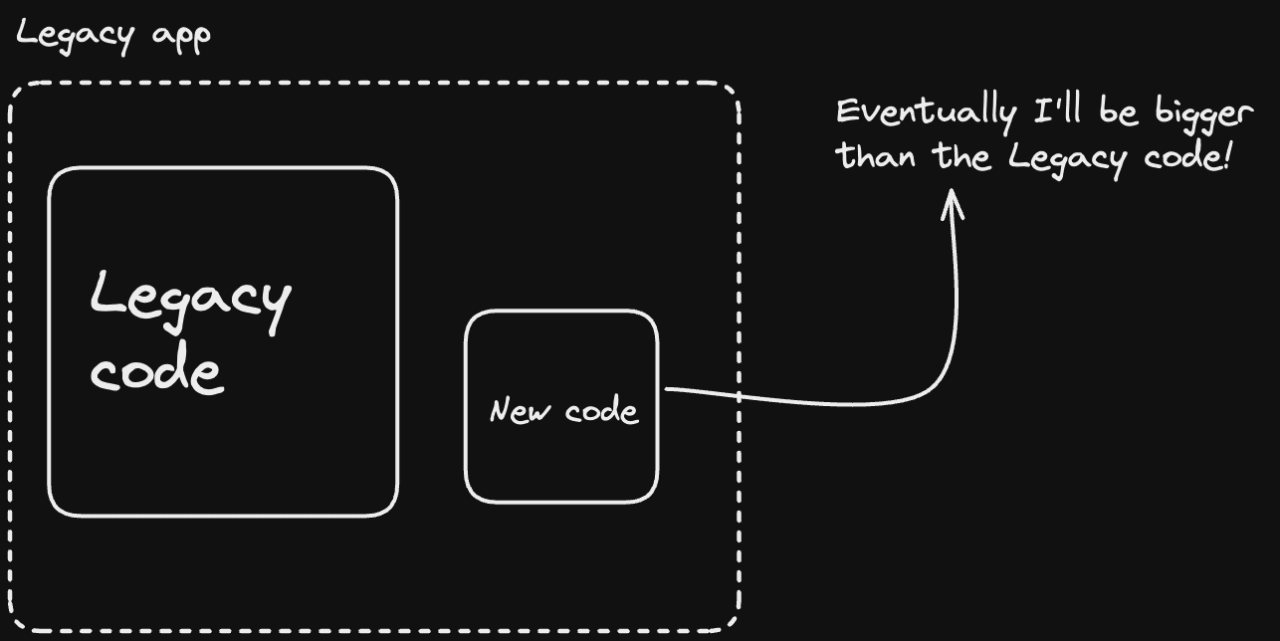

Now what do I mean by phased migration? Well just that… you migrate things… in phases 🤣. Kidding aside, a phased migration is one in which where we pick particular pieces of functionality/pieces of the codebase and start rewriting (migrating) them over to an isolated area (the “clean” area) in a manner such that they can still be consumed by the legacy bits of the application.

The phased migration I’m in favour of is one in which we start by picking out leaf nodes and working our way up the depedency tree. Rewriting entire routes or large components of an application is no easy feat and will require turns of time, however, if you break down the depedency tree into leaf nodes and start leaf by leaf, pretty soon you’ll have rewritten quite a large chunk of your codebase without you even realizing it.

After the completion of the leaf nodes, we move up to the parent nodes and begin migrating those over to the new paradigm. It’s a recursive cleanup of tech debt! There’s a lot of different ways this manifests in a codebase and I’ll leave the implementation up to you, but if you’re interested in how I’m attempting to do it at my current workplace, it’s via NX. It’s actually quite easy to plop NX into an existing application and the suite of tools it ships with and sensible defaults they provided you really make it easy to get started partioning out your codebase into “legacy” and “new”. With NX, anything that’s inside the libs directory is considered new and anything that’s inside of the src directory would be considered legacy.

The level of effort thats associated with this migration strategy is lower than a ground-up rewrite but the trade-off is that it’ll take way longer to have reach a state of minimal tech debt. Regardless, engineers will end up being happier since they are getting to write shiny good clean code and the business will stay happy because we didn’t have to throw everything that was written a few years ago into the trash.

How Did Nx Help with My Tech Debt at Work

The code for my works primary project exists in an src folder. There are a ton

of components, business logic, and state management files spread across this one

directory. Not only that, but the project itself was also configured to use

tslint and enzyme; both libraries that have been deprecated and should no

longer be used.

The way in which NX enabled me to start writing brand new features using modern tech while not having to migrate every component at once was via the usage of nx libs. NX is a suite of monorepo tools that provides users with a CLI to generate new libraries, in addition to having a cache that stores the result of various output commands (like your test and lint commands).

Once my colleagues and I had agreed to break our project into domains and

subdomains, we created separate NX libs for each subdomain. For example, we have

a product-presentation domain, a search domain, and… sigh, an ads

domain; each domain was assigned a corresponding lib.

The command to generate a react lib is: npx nx g @nx/react:library.

Another thing that NX helped us to do was enforce module boundaries. In the

legacy src folder, presentational components are coupled with data access

components and utility functions are scattered all over the place. By embracing

NX’s prescribed best practices and

Project Boundaries my

team and I were able to enforce best practices by making engineers embrace the

creation of cohesive units. The enforcement happens at the linting level

(eslint will yell if you don’t follow proper module scoping) and at the PR

level; a combination of man and machine 😆.

NX is deserving of its own blog post and I can’t do it justice in this single entry alone. Please standby for me to give a meetup presentation and record it.

How Do I Manage Tech Debt

Tech debt comes and goes; accept that it exists and that it’s just something that you need to manage. There’s two things I know for sure when it comes to tech debt; tech debt always comes back (and that’s okay 😊) and tech debt comes back at an excelerated rate if teams do not have a sense of ownership over their destiny. Truly, autonomy and responsibility are two factors that can help contribute to keeping tech debt at pay.

I slept and dreamt that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy.

It really comes down to process, not discipline. I repeat, do not rely on discipline to maintain code standards and to keep tech debt at bay. Discipline breaks down and engineers tend to skew towards laziness and for these reasons alone, relying solely on discipline is an incorrect approach toward software development. We need to put tooling in place (like linting, proper code reviews, codeowner files) that enables us to embrace a coherent approach to software development. In fact, these things are not new concepts; codeowners have been a thing on github since 2017!

Closing Thoughts

Hopefully you found this post helpful! I’m a novice at handling technical debt but I’m grateful for having had the opportunity to share my experience with you. Hopefully it’ll give you some hope when you’re dealing with your own version of “Frankenstein”… remember, fire is not always the answer! 😆